When Donald Trump bragged in September 2018, that the Black unemployment rate had fallen to “the lowest number in history,” he (be it out of ignorance or to intentionally mislead), falsely equated a single economic figure to overall increasing prosperity. Without any historical context, it’d be easy to fall victim to this rhetoric. However, when America’s long legacy of institutional racism is accounted for, it’s clear that simple economic figures and statistics barely scratch the surface in regard to the persistent race-related disparities plaguing communities across the country.

During this time of crisis brought on by the coronavirus pandemic, the continued existence of racial health disparities has become blindingly apparent. As the earliest statistics related to COVID-19 trickled in at the start of April, a disturbing trend emerged: Even in cities and states where Black people were far outnumbered by Whites, they were more likely to contract and die from the virus. In Milwaukee, where 26% of the population is Black, 81% of those who died were Black. Early data from Chicago painted a similar picture: In a city where the Black population hovers around the 30% mark, 70% of local deaths occured in the Black community.

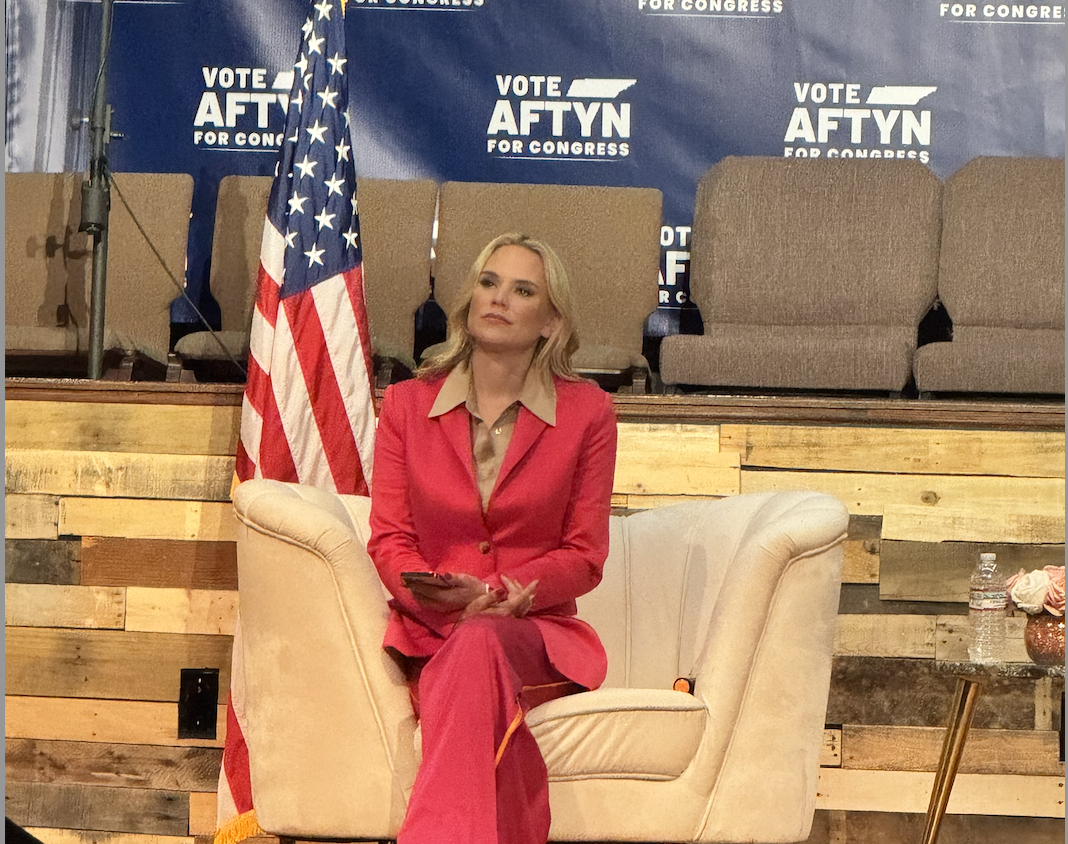

According to Dr. Joseph Webb, CEO of Nashville General Hospital, the major cause of these disparities lies “primarily among upstream, policy-related affairs that produce downstream conditions including food insecurity, housing issues, access to healthcare, and educational attainment.”

These factors, which Dr. Webb classifies as “Social Determinants of Health,” may “drive the way coronavirus impacts communities differently.” These factors also help determine who is or isn’t considered to be an ‘essential worker’ in the age of coronavirus. These oftentimes low-wage jobs include factory and grocery store workers who are in close proximity with others, cannot work remotely, and are therefore on the frontlines of the pandemic. Not only are Black people more likely to work these kinds of jobs, but the underlying, chronic conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes that make a person more susceptible to coronavirus complications are also more common in the Black community.

Dr. Webb warned against the dangers of blaming the victim for the downstream effects that result from policy decisions. “People across racial groups engage in unhealthy behavior, but minorities–particularly Blacks–are hurt the most.” This contrasts heavily with Surgeon General Jerome Adams’ now highly-criticized statement in which he called on Black and Brown people to “step up” and avoid alcohol and drugs to minimize the impact of the virus, saying, “ Do it for your granddaddy, do it for your big momma, do it for your pop-pop.” While individuals can certainly take steps to mitigate the negative effects of these policy decisions, Dr. Webb believes that addressing the “real issues and upstream causal factors, as opposed to simply treating the symptoms,” is the best way to narrow racial health gaps.

“We must allow research and data to inform policy,” he adds. “We’ve known about the implications of the Social Determinants of Health for a long time, but we tend to ignore it and then wait for the next problem.” Dr. Webb explained how creating more health literacy programs, improving access to healthcare, and increasing access to healthy foods and fitness centers, and boosting educational attainment can help strengthen vulnerable communities. He also cautioned against continuing the pattern of denying health disparities, saying, “ Unless we own it, it will resurface with each crisis.” The time to prepare vulnerable communities for the inevitable next crisis, is now.