Opinion by Thomas Balcerski

Editor’s note: Thomas Balcerski is author of “Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King” (Oxford University Press). He tweets @tbalcerski. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. Read more opinion at CNN.

(CNN) — Once more, the upcoming Democratic debates will offer voters a chance to see the party’s presidential hopefuls in action. Divisions over ideology and identity have defined the race: the liberals debate the moderates over policy questions, the Northeasterners quibble with the Midwesterners about attracting voters, and the young needle the old over who should lead. The one thing on which the Democratic field seems to agree is that their party fundamentally differs from the politics and policies of Donald Trump.

By adopting a defeat-Trump-at-any-cost strategy, the Democrats have missed a key lesson from the past: being the party of opposition and the promoters of mere change will only carry you so far. The approach may yield electoral success in the short-term, but it fails to create lasting change and, worse still, does nothing to communicate an effective vision for the future of this country to the voting public. By not recognizing that their enemy is not so much Donald Trump as their own myopic commitment to defining themselves in opposition to him, Democrats risk the future of the country with their lack of vision.

Here is where history can help. By studying the campaign messaging and strategies from prior presidential elections, the Democrats can help to clarify what has worked well and what has failed miserably in the past. As it turns out, the history of the Democratic Party is chock full of examples of both.

During the Great Depression, the Democrats seized power under the charismatic leadership of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In the election of 1932, Roosevelt ran less against the incumbent, Herbert Hoover, than he did for a program of visionary transformation of America. During the campaign, Hoover attempted to brand Roosevelt as a radical; rather than issuing a direct rebuttal to these attacks, FDR instead rejected the idea that the ongoing economic downturn could not be corrected. This did not prevent Roosevelt from drawing a contrast between his policy ideas and those of the incumbent: “Here is the difference between the President and myself,” he declared, “I go on to pledge action to make things better.”

Dubbed the “New Deal,” Roosevelt’s vision effectively set the political agenda for a generation of American politics. Harry Truman looked to expand the reach of the New Deal with a “Fair Deal” that promised progress in the areas of civil rights, education, health care, welfare, and more. Although he did not fulfill all its stated aims, Truman set the tone for later presidents: Both John F. Kennedy’s “New Frontier” and Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” programs set forth the idea of a safer, more inclusive America that would be more humane to its citizens. These Democrats stood for a vision of America that included government as a partner and not simply against their opponents.

In contrast, the Democratic Party of the mid-20th century faltered. Adlai Stevenson, a brilliant tactician and strategist, helped to formulate the “Domino Theory” as a way to stop the spread of communism around the world. But as the party’s candidate in 1952, he could not present a coherent plan to end the unpopular Korean War. Dwight Eisenhower, a war hero, promised to do so and ran on the simple phrase “I Like Ike.” He won in a landslide. In 1956, Stevenson was given a second chance and this time opted to run against Eisenhower’s age (he was 66) and ill-health (he had suffered a heart attack). Once again, the American people decided that they liked Ike.

The election of Richard Nixon in 1968 and the subsequent breakup of the New Deal coalition set the Democratic Party adrift. In time, Democratic hopefuls seemed to turn to the theme of “change” as the political answer to Republican rule. The candidacies of Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton respectively promised to bring “Leaders, for a Change” (1976) and “For People, for a Change” (1992). On the surface, they were charismatic young leaders in whom Americans felt comfortable placing their full faith.

In retrospect, the change that they offered did not last. While in office, Carter turned against his own optimism for America’s future and instead warned of a “malaise” afflicting the country. Clinton’s bold vision for America was derailed by mismanagement (especially on health care reform) and his personal failings as a leader.

As the 21st century began, the Democrats floundered. Al Gore ran on the concept of “Leadership for the New Millennium,” but the legacy of Bill Clinton likely convinced voters to embrace the “compassionate conservatism” of George W. Bush instead. In 2004, John Kerry’s vague promise of a “Stronger America” could not defeat Bush’s continued promise of a “More Hopeful America.”

Yet once more, also in 2008, the Democrats chose a candidate who espoused “Hope” and “Change We Can Believe In.” The country responded by overwhelmingly electing Barack Obama as the nation’s first African American president. The electoral backlash of the 2010 midterms limited the party’s vision once again and foretold some aspects of the rise of Donald Trump. In 2016, “I’m With Her” was not a strong enough vision for America’s future to counter the more hardline message of “Make America Great Again.”

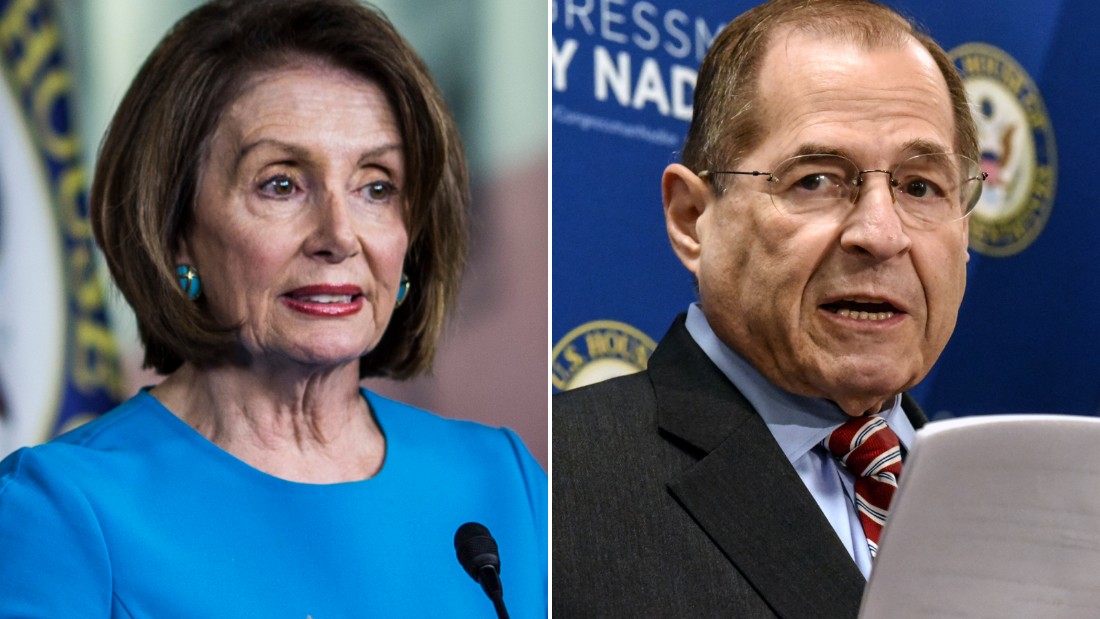

The Blue Wave of 2018 once more showed that some in the Democratic Party can present a better message to the American people than their Republican counterparts. Yet so far, in the 2020 presidential campaign, the party has continued to rely upon the idea of defeating Donald Trump as its most salient message. Americans should choose Democrats as the lesser of two evils, they seem to be saying. Jill Biden has practically said as much.

This strategy has almost never worked in the long term, and it will almost certainly fail, as it did in the election of 2016, if voters do not like the party’s candidate selected in 2020. Democrats — both moderates and progressives — should be wary.

Whoever emerges as the Democratic candidate in 2020 would instead do well to remember the words of FDR, who as a candidate himself declared at a 1932 commencement speech: “The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

The Democrats have been at their best when they lead change from an inclusive and bold vision for the future, one not predicated on defeating the current occupant of the Oval Office. They should look, as FDR once said, to try, rather than simply to oppose.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2019 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.